Interstate conflict has dramatically decreased since 1946 while intrastate conflict has skyrocketed, said Dr. Jon Wilkenfeld, director of START’s ICONS Project, during a recent talk on the “Principles of International Negotiation” based on his book "International Negotiation in a Complex World.”

“Part of the reason international negotiation has become more complex is that there has been a dramatic shift in the modern era from traditional interstate conflicts toward intrastate conflicts and transnational issues, introducing new players, processes, issues and opportunities to an already multidimensional and high-stakes endeavor,” Wilkenfeld .png)

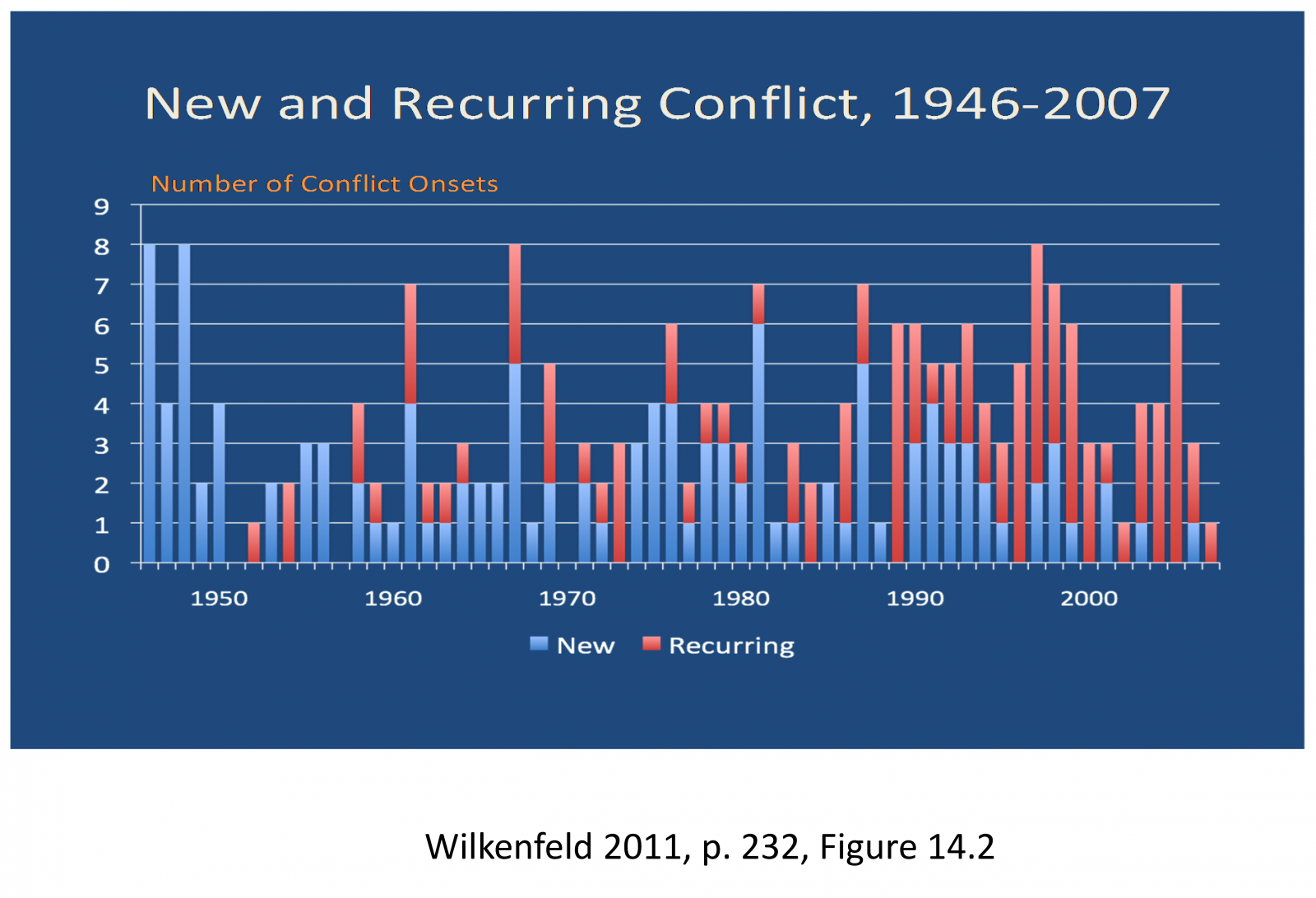

The need for negotiation – and understanding the key international relations concepts on which negotiations should be based – is becoming even more apparent as trends for global conflicts have changed: new conflicts are relatively rare, while conflict recurrence is the norm. In the past couple of decades the number of recurring conflicts have increased significantly, and they now far exceed the number of new conflicts set in the mid-1990s.

“Recurrence is now by far the most common form of conflict,” Wilkenfeld said. “This could indicate that we’re not doing a great job actually resolving conflicts and that we’re falling short in negotiations. Negotiation is how we resolve conflicts.”

Wilkenfeld explained the key characteristics important for evaluating an international negotiation with respect to the actors, issues, and process. For example, it is important to clearly identify the number of actors/coalitions engaged in the negotiations, have a general understanding of the cultures involved and get a sense of their capabilities as well as their relative power in the particular conflict situation.

“The more powerful a country is, the greater its ability to get what it wants,” Wilkenfeld said. “But all power is relative.” Thus, the context in which an actor is exerting its power and persuasiveness is therefore essential to understanding negotiation outcomes.

Wilkenfeld also highlighted some factors that increase complexity in negotiation: actors are added; additional issues are linked; there is a lack of consensus about negotiation goals; negotiators do not have decision-making authority; and the situation is perceived as a crisis, increasing pressure on negotiators.

Other factors such as changing goals and preferences of the

negotiation team, a mixture of conflictual and cooperative motives and goals, and not enough knowledge about the other parties’ goals and preferences, can further complicate a negotiation.

“It may seem counterintuitive, but one way to simplify the process may be to add more issues to the table,” Wilkenfeld said. “Sometimes the more issues you have, the greater the possibility you can move from zero-sum to a positive-sum or win-win situation in negotiations.”

Another key element in any negotiation is the time constraint, Wilkenfeld said. Time constraints can be different for each actor and thus influence how they negotiate. However, one thing remains true across all negotiations:

“You know what they say about 90 percent of an iceberg being under the surface? Well, 90 percent of an agreement occurs in the last 10 percent of the negotiation,” Wilkenfeld said.

Wilkenfeld said that he and his co-authors wrote the book to provide students with the tools needed to analyze why negotiations succeed or fail, and to provide a basis for understanding the impact of complex multilateralism on traditional negotiation concepts such as bargaining, issue salience, and strategic choice.

Wilkenfeld and his co-authors – Brigid Starkey and Mark Boyer – use an easy-to-understand board game analogy as a framework for studying negotiation episodes while including a rich array of real-world cases and examples to illustrate key themes.

“We focus on topics such as the intensity of crisis situations for negotiators, the role of culture in communication, and the impact of domestic-level politics on international negotiations,” Wilkenfeld said. “However, the best way to learn something is through doing. We included exercises and learning approaches that enable students to understand the complexities of negotiation by engaging in the diplomatic process themselves.”

To augment these resources in the book, the ICONS Project is offering a special discount on negotiation simulations for instructors who want to give their students the opportunity to experience the concepts and practice using the skills introduced in “International Negotiation in a Complex World.”

To learn more about “International Negotiation in a Complex World” or to purchase the book, visit https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781442231085.