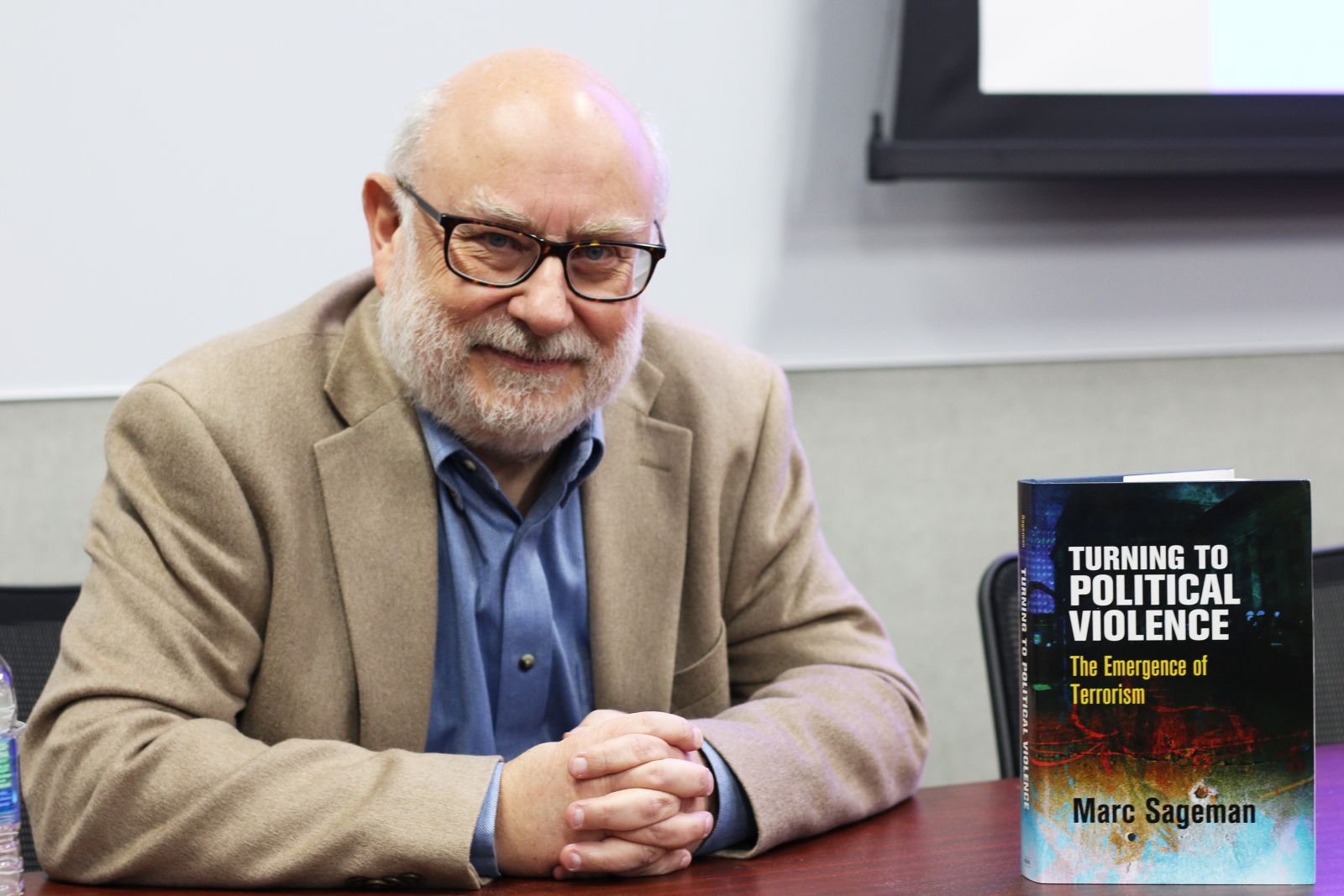

Last month, terrorism scholar and former CIA officer Dr. Marc Sageman presented a lecture entitled, “Emergence of Terrorism: A Dialectical Model” at START headquarters.  Both his lecture and recent book, “Turning to Political Violence: The Emergence of Terrorism,” examine how the complex interactions between a state and disaffected citizens can lead some to disillusionment and moral outrage — and others to mass murder.

Both his lecture and recent book, “Turning to Political Violence: The Emergence of Terrorism,” examine how the complex interactions between a state and disaffected citizens can lead some to disillusionment and moral outrage — and others to mass murder.

“One man’s terrorist really is another man’s freedom fighter. It is vital who defines whom,” Sageman said.

A majority of the book talk focused on Dr. Sageman’s explanation for how terrorism emerges. Terrorist groups begin as communities with legitimate grievances. State intervention — such as military invasions, systematic oppression or police crackdowns — politicizes those grievances. The intervention also alienates those with grievances and creates what Sageman calls a “Political Protest Community.” As the aggrieved fixate on the perceived threat of violence from state actors, they strengthen their ties to other members of the political protest community and their identity within that community. This further divides society into a moderate majority out-group and an increasingly-ostracized political protest community in-group.

Sageman notes that these communities are not innately dangerous; only the most devoted members are driven to political violence under certain conditions.

Sageman notes that these communities are not innately dangerous; only the most devoted members are driven to political violence under certain conditions.

First, the conflict escalates as both community and state figures begin using violent rhetoric and an “us vs. them” mentality. Second, political protest community members become disillusioned by the formal justice system and experience moral outrage as a result of their disillusionment. The most devoted members will redouble their efforts to fight the perceived opposition, creating an extreme inner circle protest community. This inner circle typically commits the first acts of violence against more moderate group members who are not willing to remain engaged. Finally, members of the inner circle craft a martial group identity. Socially, they engage in paramilitary activities, such as “camping, roughing it or paintball.” Spiritually, they idolize martyrdom and view themselves as “special, different, history makers and vanguards of the revolution,” according to Sageman.

The big paradox? Once that inner circle commits an act of political violence, both the state and its citizenry at large tend to focus only on the group’s terrorist act and not their legitimate grievances. After an attack, state oppression and negative representation of all members of the political protest community simply restarts the cycle of radicalization.

As the child of Holocaust survivors, Sageman has an intimate understanding of political violence from victims’ perspectives. Only after reading Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men in his course of study at Harvard’s sociology program did he realize that studying perpetrators would yield more insight into counter-terrorism and de-escalation strategies.

“Without perpetrators, there would be no victims,” he said.

Ever since, Sageman has sought to interrupt the cycle of radicalization by studying how terrorists are driven to perpetrate violence. During the lecture he argued for several de-escalation techniques, most notable of which is the inclusion of political protest community members in mainstream society. Their grievances must be seriously considered in the formal legal system. State action against singular violent group members must be proportional, non-violent and even-handed. Academics and counterterrorism practitioners must also be trained not to reduce those with grievances into one-dimensional stereotypes. Of equal importance, non-violent community members and violent inner-circle extremists must not be conflated.