The following is part of a series of thought pieces authored by members of the START Consortium. These editorial columns reflect the opinions of the author(s), and not necessarily the opinions of the START Consortium. This series is penned by scholars who have grappled with complicated and often politicized topics, and our hope is that they will foster thoughtful reflection and discussion by professionals and students alike.

START’s Domestic Radicalization team has produced the Bias Incidents and Actors Study (BIAS) dataset.[1] BIAS is a first-of-its-kind representative dataset on perpetrators of hate crimes in the United States. That is surprising given that Congress has mandated data collection on hate crimes since 1990 and that the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program captured data on over 7,100 hate crimes in its most recent data release covering 2018. Despite this longstanding investment in data collection and the high numbers of incidents documented, the government has focused less attention on perpetrators, prevention and responses related to hate crime than on terrorism, which occurs much less frequently. For criminological, legal, bureaucratic and social reasons, governments at the federal, state, local and tribal levels have addressed hate crimes as a “local” issue distinct from terrorism, while treating terrorism as a national security issue. This has to change; hate crime is a national security issue.

While the intellectual distinction between terrorism and hate crime is not arbitrary, terrorism and hate crime are overlapping phenomena. Hate crimes are understood as crimes in which the victims are targeted because of their perceived identities, and terrorism is understood to mean ideologically motivated violence intended to have a psychological and political impact on an audience beyond the physical target of the attack. It may be challenging to know if a perpetrator’s motivation was to harm just the victim or to harm the victim and affect an audience beyond the victim. Hate crime perpetrators may desire both, but regardless, targeted communities feel the impact. The fact that some hate crimes are mass casualty attacks reinforces the harm that hate crimes cause more generally. Our data reflect this overlap, as approximately 30 percent of the individuals in our hate crime database also appear in a companion START dataset of political extremists.

Given that both the perpetrators of hate crime and terrorism are ideologically motivated offenders, they can and do emerge from the same online and in-person social networks. These shared social networks greatly amplify hate crimes after the fact. Even if a given hate crime was not premeditated or conceived as part of a campaign of violence, it can achieve the same psychological and political impact as an act of terror.

Hate crimes also create opportunities for malign foreign influence operations to amplify xenophobia, racism, gender identity bias, anti-Semitism and ultimately polarization, at orders of magnitude more frequently than terrorism. In each of the last four years, the United States has experienced over 60 terrorist attacks according to START’s Global Terrorism Database. By comparison, the FBI reported 7,120 hate crimes in 2018, each one an invitation for opportunistic foreign influence operations to tear the fabric of our society. While influence operations amplify the harms caused by hate crimes, they can also sew conspiracy theories, nurture prejudices and dehumanize potential victims to increase the likelihood of future American-on-American violence.

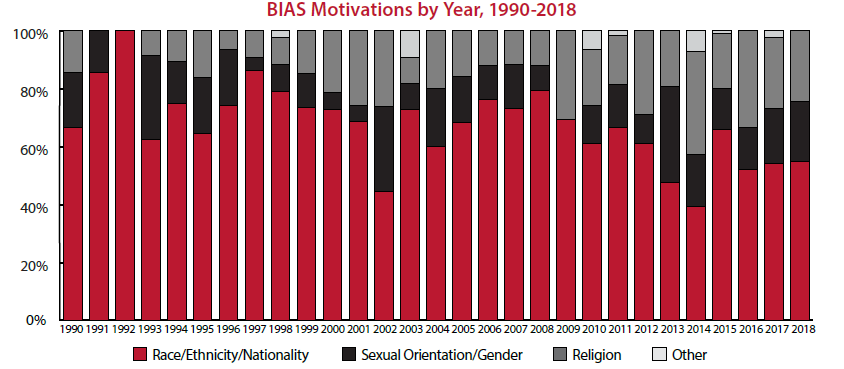

Moreover, by bifurcating hate crimes from terrorism, we create incomplete, inaccurate and misleading threat assessments that already suffer from the dubious intellectual distinction between international terrorism and domestic terrorism. Domestic terrorists are already more numerous, lethal and active than international terrorists in the United States, but the disparities are exacerbated when we consider that over 90 percent of the perpetrators in our hate crime database targeted people of color, religious minorities and/or LGBTQ people. These offenders were motivated by the prejudices that circulate in domestic extremist milieus and throughout society more generally. Based on incomplete threat assessments, our professional security community focuses on a small percentage of ideologically motivated acts of violence in the United States, primarily those carried out by international terrorists and “homegrown violent extremists (HVEs).” This leads to poor resource allocation decisions, disjointed legal and bureaucratic responses, and most importantly, markedly higher success rates for violent domestic extremist plots when compared with violent international and HVE plots.

Moreover, by bifurcating hate crimes from terrorism, we create incomplete, inaccurate and misleading threat assessments that already suffer from the dubious intellectual distinction between international terrorism and domestic terrorism. Domestic terrorists are already more numerous, lethal and active than international terrorists in the United States, but the disparities are exacerbated when we consider that over 90 percent of the perpetrators in our hate crime database targeted people of color, religious minorities and/or LGBTQ people. These offenders were motivated by the prejudices that circulate in domestic extremist milieus and throughout society more generally. Based on incomplete threat assessments, our professional security community focuses on a small percentage of ideologically motivated acts of violence in the United States, primarily those carried out by international terrorists and “homegrown violent extremists (HVEs).” This leads to poor resource allocation decisions, disjointed legal and bureaucratic responses, and most importantly, markedly higher success rates for violent domestic extremist plots when compared with violent international and HVE plots.

The undercounting of “domestic” extremist threats has potentially dangerous implications. For instance, white supremacists, who adhere to and promote many of the prejudicial beliefs that motivate hate crimes, are increasingly espousing revolutionary ideologies including calls for a racial holy war, a second civil war and conspiracy-fueled violence against a partisan “deep State.” This revolutionary turn is concerning given that domestically and internationally, white supremacists are adopting mass casualty tactics with greater frequency. Finally, especially since 2015, an increasing percentage of American extremists have been motivated by anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant xenophobia. This ideological shift has allowed white supremacists in the United States to interact and find common cause with foreign white supremacists, for whom xenophobia is a defining feature, more so than in the past. Just as the internationalization of violent jihadism has provided extremists with access to training, financing and recruiting opportunities, safe havens from which to plot attacks, and combat experience in conflict zones, the increasing internationalization of white supremacy poses enduring national security risks.

Finally, treating hate crimes differently from terrorism perpetuates systemic racism and undermines public safety. Our current posture systematically and rhetorically undervalues the victims of hate crimes, despite those people representing the majority of victims of ideologically motivated harm. This failure exacerbates distrust between underrepresented minority communities, the criminal justice system and the government more broadly. The perception that some lives appear to hold less value than others adds to the grievances and polarization that invite foreign influence operations and increases the attractiveness of extremist narratives that malign government and law enforcement institutions.

The Biden administration must engage in holistic and integrated threat assessments of ideologically motivated violence and allocate resources accordingly. As it currently stands, for example, the FBI Criminal Division investigates hate crimes and the Counter Terrorism Division (CTD) investigates terrorism, with a fusion cell liaising between the two. During Congressional testimony in September 2020, FBI Director Wray highlighted a successful disruption coordinated by this fusion cell which was, “able to prevent a potential terrorist attack before it occurred and, for the first time in recent history, make a proactive arrest on a hate crimes charge [emphasis added].” It stands to reason that violence prevention programs and criminal justice disruptions are similarly applicable to both categories of perpetrator. The fusion cell is to be congratulated, but this novel instance may be the exception that proves the rule.

The FBI reports conducting “hundreds of these [hate crimes] investigations every year.” By comparison, data and testimony provided by the FBI in 2019 indicated there were approximately 850 domestic terrorism investigations underway, and that these represented 20 percent of CTD’s caseload, with the balance comprised of international terrorism cases. Those terrorism investigations benefit from approximately 200 FBI-led Joint Terrorism Task Forces across the country and the FBI’s two International Terrorism Operations Sections located at the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), which provide direct connectivity to the intelligence community’s international terrorism infrastructure. The FBI recognizes the overlapping nature of the threat, and should be empowered and encouraged to structure itself and allocate resources accordingly.

To reverse the perception that terrorism and its victims are more important than hate crimes and its victims, the administration should not mention terrorism in a sentence without also mentioning hate crime. The distinction is as rhetorically counterproductive as it is pragmatically counterproductive. Both terrorism and hate crimes harm, injure and kill Americans. They both drive polarizing wedge issues deeper into the fabric of our society, and both embolden new and existing enemies, both foreign and domestic. “Terrorism and hate crime” have no place here, and both are a national security issue.

[1] I would like to thank Mike Jensen, Elizabeth Yates, Sheehan Kane, and our many student interns for their pioneering work on the BIAS dataset, as well as their input on this Discussion Point article. Any errors or shortcoming found here, however, are mine.

Note: An earlier version of this piece cited number of hate crime offenses, rather than incidents, from the FBI's report. The numbers are clarified here. (11/16/2020)

William Braniff is the Director of the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) and a Professor of the Practice at the University of Maryland. He previously served as the director of practitioner education at West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center (CTC) and an instructor in the Department of Social Sciences. Braniff is a graduate of the United States Military Academy.