“Would we care about al-Shabab in Somalia the way that we do right now, if it was not an Al-Qaeda affiliate? If you were talking about an insurgent group in Afghanistan, even one that was particularly brutal to its civilians that were Uzbeks, Pakistanis and Afghans, that wanted to challenge the Taliban and conducted attacks against the Afghan government, would we be using the mother of all bombs on this terrorist organization if it was not associated with the Islamic State? The reality is--we probably would not. These relationships have defined how we see these organizations.”

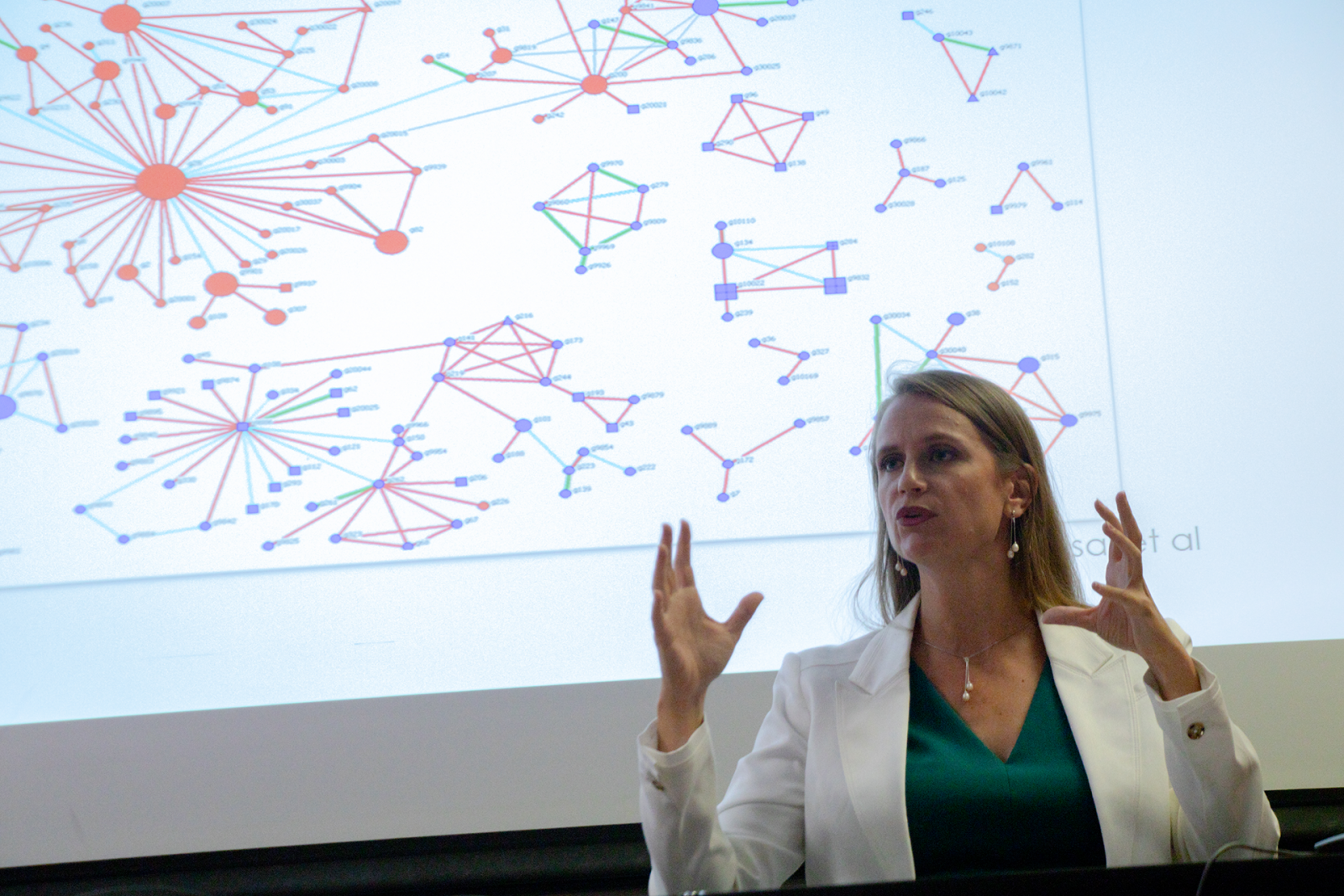

Tricia Bacon, a researcher, author, and assistant Professor in the department of Justice, Law and Criminology at American University, delivered a presentation about her recently published book on the alliances within the community of terrorists on June 27 at START.

H er presentation, titled after her book, “Why Terrorist Groups Form International Alliances,” was centered around alliance networks, the risks and rewards of these communities, and the future of alliances in the global terrorism community.

er presentation, titled after her book, “Why Terrorist Groups Form International Alliances,” was centered around alliance networks, the risks and rewards of these communities, and the future of alliances in the global terrorism community.

“As early as 2013, the U.S. counterterrorism strategy incorporated the idea that to defeat the terrorist organizations that were the biggest threat to the U.S., we had to divide them from each other and break those relationships,” Bacon said.

Bacon began discussing the idea of what an alliance is and their importance in the validity of the global terrorism community. According to Bacon, the existing research shows that terrorist groups that have alliances are more lethal in their attacks, they are more likely to seek weapons of mass destruction, and they are more capable of recovery from setbacks, like the loss of a leader.

She went on to discuss the benefits of having an alliance. These organizations can have tangible rewards like, “money, weapons and training,” which provide them with more tools to develop their inventory and strategies. However, she also discussed the intangible rewards like the reputation some organizations create after forming an alliance because “being associated with these organizations allows for groups to better align with something that has more resonance to their cause.”

Bacon explained that these alliances share best practices and lessons with one another because it helps them prove their position within the global terrorism community. The community is like a map of networks of alliances, but Bacon said she was interested in the few organizations that were “disproportionately involved in these alliances” because those are the ones that are often sought out in becoming partners in an alliance. These groups, which she calls alliance hubs, have the capability to provide the most benefits in a partnership, which attracts many other groups and making them central in alliance networks.

“These are the relationships that involved cooperation and expectations of coordination and consultation in the future,” Bacon said. This idea of future expectations is what differentiates alliances from cooperation, which is important to distinguish because alliances have demonstrated staying power in the contemporary environment.

Bacon concluded that shared ideologies or common enemies are not the cause of alliances, but rather they guide partner selection - leading groups to cluster towards the previously mentioned hubs. Instead, organizational deficiencies cause groups to seek allies. Alliance hubs are groups well positioned to address those weakness and that share ideologies and enemies with numerous other group. Hubs foster alliances and sometimes even spawn other hubs. In the current environment, al-Qaida and the Islamic State are hubs that define the terrorist threat. Bacon sees opportunities for disrupting these relationships before they form, particularly by stymying trust and early cooperation.

Bacon worked in counterterrorism for more than 10 years at the Department of State in the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, the Bureau of Counterterrorism, and the Bureau of Diplomatic Security. She is a non-resident fellow with George Washington University’s Program on Extremism and she has conducted research and analysis on counterterrorism in South Asia, North Africa, East Africa, Europe and Southeast Asia. Her research focuses on terrorist and insurgent groups’ behavior and decision-making, U.S. counterterrorism policy, and the role of intelligence in national security.